The Art of organisational simplification

It sounds simple, just simplify your organisation, but simplifying an organisation is quite different from simplifying it. When you remove the complex processes of your organisation, it becomes simpler, but you have to wonder if you still have something useful in your organisation. Simplifying your organisation requires logic. This logic never applies to just one process but to the entire organisation to avoid sub-optimisation. It’s impressive when a process runs optimally, but if it disrupts the rest of the processes, the organisation as a whole gains nothing from it. Real organisational simplification can only happen when the entire organisation moves in the same direction, interdisciplinary, and therefore with an organisational strategy.

Organisations and Organising

It’s useful to first establish what an organisation is. An organisation is a “collaboration between living beings (organisms) pursuing a common goal through behaviour coordination.” Many people see significant differences between companies and non-profit organisations, associations, foundations, institutions, enterprises, political organisations, NGOs, or ad hoc coalitions like neighbourhood barbecues, planned demonstrations, or charity runs. However, they are all collaborations between people pursuing the same goal and are therefore all organisations.

Old Habits in Organisations

When people organize, especially with the intention of starting a business, they often resort to theories and practical examples. Even startups, at their inception, establish departments for procurement, production, sales, accounting, IT, etc. You might think it’s better to steal good ideas than to come up with bad ones, but that doesn’t apply to organising. Large organisations that are structured with departments and complex processes have evolved over time because they couldn’t adapt optimally to changes. Over time, it has become an art to logically guide a customer request through the organisation. The structure of that time, with all its contrivances to adapt it to the present, makes the organisation unnecessarily complex. Through knowledge transfer to successors, behaviour is taught (copied) instead of being learned on its own. Consequently, the behaviour of people within processes and (thus) organisations often does not align with the organisation itself. The organisation adapts (adapts) to the environment, making the greatest simplification not external but internal to the organisation itself.

Organising is a Verb

To break free from old thinking, it’s important to realise that organising is a verb. It’s a continuous process of activities that must align for a specific purpose. Activities vary per process, and processes vary per customer request (for example, a product). Therefore, an organisation must continuously organize instead of establishing an organisation and then aligning the customer to it.

This doesn’t mean you should do everything a customer asks for, but it also doesn’t make sense to keep producing cassette tapes in this day and age. An organisation should not be dogmatically structured but should naturally remain flexible to think and work in the present.

Organising Boils Down to Two Things: People and Processes

Where the definition of organising speaks of ‘beings’ or ‘organisms’ because aligning behaviour with a common goal applies to all forms of organisations, including living organisms, we’ll stick with people here for simplicity’s sake.

The crucial part here is aligning behaviour. Alignment can occur in various ways: by command, request, shared interests, coercion, seduction, love, reward, etc. The most common within an organisation is ‘reward’ because that’s what an employee gets for conforming their behaviour to the organisation’s interests. Conforming behaviour to align it for the organisation’s benefit creates a process: a series of aligned behaviours.

People

In daily life, everyone exhibits behaviour that can be traced back to ’emotion,’ think of ‘kind,’ ‘helpful,’ ‘friendly,’ ‘busy,’ etc. These are (mostly) relatively easy to manage within an organisation, as long as you take good care of your people. It sounds simple, but unfortunately, it’s not always done well. This is where culture comes in, the sum of all behaviours.

Once this basic condition is met, a deeper look can be taken at behaviour as activity within the organisation, such as how actions are performed in making a product or how work is done within a department. The organisation itself holds the key here; this is ‘learned behaviour.’ The answer to ‘why do you do it this way?’ is nine times out of ten: “because that’s how I learned it” or “that’s how it was shown to me” or (even worse) “someone with an MBA designed it that way, so we listen to it.”

Learned behaviour is behaviour that people exhibit because it’s always been that way, without questioning whether it’s the right behaviour for the organisation. It has become so commonplace that no one questions why anymore.

Processes

To observe whether a series of aligned behaviours leads to a good result, the tangible output of a process is examined, what comes out of a process, such as ‘products,’ ‘semi-finished goods,’ ‘services,’ ‘strategy,’ etc. These are relatively easy to observe; any self-respecting organisation manages the quality of its output.

The challenge lies in the intangible output of a process regarding process design. It’s still possible to get a good output from a poorly designed process. The process is just not efficiently and effectively designed, leaving opportunities untapped. This inefficiency can be observed through process information, the so-called intangible process information. Think of inefficiency in time per unit, materials per unit, money per unit, people per unit, machines per unit, etc., but also the loss of output quality.

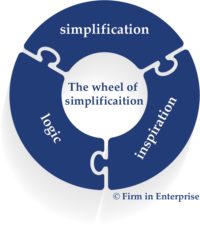

The Approach of Firm Simplification

We’ll leave out the components ’emotion’ in behaviour and ‘tangible output’ in processes and focus on ‘learned behaviour’ and ‘process information.’

Learned Behaviour

With the well-known static theories of gurus like Porter, Deming, Mintzberg, Kaplan, etc., you only end up with a standard organisation design where learned behaviour is the guideline. Overcome by the zeitgeist and modern techniques, large organisations that still organize this way see startups coming along and dethroning them. So, it’s not wise to copy them.

To prevent learned behaviour, an organisation should be better designed by people who know how to use logic instead of (old) knowledge. This is also why entrepreneurs who start with passion succeed much more often and better than entrepreneurs who start with the goal of setting up an organisation to make money. The latter group quickly resorts to theories and examples symbolising learned behaviour.

The solution for setting up a new organisation is relatively simple, the challenge lies in simplifying existing organisations. To combat learned behaviour, we can learn from the most famous philosophers.

Ask questions like Socrates: continuously ask the ‘why question’ and keep wondering why something is the way it is, and only stop questioning when there is a clear and well-thought-out intention behind the behaviour.

Dare to think like Plato: constantly question which reality you are looking at. Every problem, every challenge, every situation has multiple perspectives and should therefore be viewed through different lenses. After all, there are many more (external) factors that play a role in how learned behaviour arises. It may sound difficult again, but it isn’t.

Learn to observe like Tao: the art of doing nothing (then you see the behaviour of others without being influenced by your own), the art of observation (then you see more than just deviations from your own expectations), and the art of accepting what you see (then you can make a good plan, namely to stimulate good behaviour and ignore bad behaviour).

Dare to reason like Aristotle: with the answer to the ‘why question’ and an objective interdisciplinary view of the situation, logic reasoning can be done. The logic that arises here is the weapon against learned behaviours.

A well-founded logical solution is inspiring to people because logic inspires! People see that things can be different and easier, making them inclined to look at their own behaviour and ask ‘why.’ By learning to look through different lenses and observing their own behaviour within the organisation.

The aligned logic that arises from this simplifies the entire organisation.

Process Information

If things go well with preventing and combating learned behaviour, logical process design will follow naturally. However, there is also information in a process that must be considered in the simplification process.

In a process, there is also information that can be used to optimize processes. This is actually killing two birds with one stone, not only is it important to have information about how things are going within the process, but the cooperation between different processes can also be monitored in this way. This information is the basis for the dashboard or the MIS (Management Information System), what we’ll further call process information.

The information within the process contains factual data such as ‘number of units per time unit,’ ‘cost per unit,’ ‘duration,’ etc., the kind of information economists like to steer on. The information for cooperation between processes is often forgotten and contains information such as ‘output versus input control,’ ‘intermediate stocks,’ but also ‘where are the responsibilities,’ ‘how do we work together,’ ‘how do we ensure collective learning,’ etc. It is therefore important to look beyond the hard economic figures because you miss the steering information between processes. This increases the risk of working on sub-optimisation per process rather than on an optimal organisation as a whole. Behaviour, process output, and process information are therefore inseparably linked and should not be interpreted separately by the Management Information System.

Naturally, process information is also obtained from the tangible output, such as: waste, material consumption, rejects, number of units, inventory size, etc.

The Danger of Experts

Now that we know that people and processes are interwoven throughout the entire organisation, it also becomes clear that the old way of thinking in departments is no longer sustainable. Both people and processes do not stop at a departmental boundary. This is why so many organisations have switched to matrix structures or project-based work. Both are transitional phases of organisations that actually want to organize themselves flexibly and naturally into logical processes. Moreover, this proves the fallacy of purely economic management of organisations because the actual process information within a process does not (necessarily) contribute to the organisation as a whole. Sub-optimisation lurks.

‘Experts’ can be right from their own point of view and yet not help the organisation as a whole progress. When experts are asked to solve problems within organisations, it often creates a dangerous situation for the organisation as a whole. Take, for example, a Six Sigma black-belt guru who is asked to turn the ‘production of chair legs’ department into a super lean department. The chair legs come out of the machine flawlessly, but they pile up in assembly because the seats and armrests are not yet arranged properly. The process information from the ‘production of chair legs’ process indicates that the manager of chair legs deserves a bonus, the managers of ‘seats’ and ‘armrests’ get a tough time in their performance reviews, and the organization incurs significant losses. And even if all production departments have been tackled by this black-belt guru, only production is lean. No chair will leave the factory anymore, but according to the system, it’s a top-notch company. The same applies to the CFO who intervenes in the organization because financial resources are insufficient and therefore becomes the new CEO. By calculating, it’s determined that the department that performs the least well and has the most expensive employees will be axed. What he/she doesn’t see from the process information with an economic perspective is that all good workers were just brought to that department to solve the internal problem. As a result, ‘coincidentally,’ the most expensive forces are also fired… champagne for the board! The following Monday, however, it turns out to be a painful hangover.

These are, of course, simplified examples, but that’s the power of simplification. In the learning process at school or when explaining things, we often simplify, but in daily practice, we’ve unlearned to see through unnecessary complex (learned) behaviors and often can’t see the forest for the trees.

The expert view can be avoided by approaching processes interdisciplinarily. The information must come from objective observations of behavior, the output of processes, and the process information; a set of information to make well-founded and logical decisions. Hence, a simplifying view from the outside (the best helmsmen), with the right questions, lenses, observation, logic, and inspiration. An approach that considers the organization as a whole can provide the organization with true simplification.

Logic Inspires!

The word logic deliberately recurs frequently because logic is always something of the present. It is logic that ensures organizations are simplified because it is the driving force for further simplification. People are inspired to look at themselves, others, and the organization through different lenses and align behavior with each other and therefore with the organization’s interests. You’ll be surprised to see what ‘simple’ improvements occur when the organization simplifies itself.

A Firm Simplifier ensures that the flywheel starts spinning by showing what unnecessary complex (learned) behavior is, teaches people to look through different lenses, and prevents sub-optimization and tunnel vision through an interdisciplinary approach. Once the flywheel is spinning and the organization is inspired to work with logic itself, further Firm Simplification is up to the organization itself. “Help me to help myself,” a quote from Maria Montessori, who in this case may be considered a philosopher of behavior. We are always available to help out again, but our goal is to help organizations do it themselves. Good for the organization’s wallet, but also for us because there are more than enough organizations that need simplification.

Personal Note

As a child, I struggled in school because I didn’t grasp the material quickly enough. Due to the way it was explained and especially the (for me) lack of sufficient context, I missed the logic of the material, so I kept pondering over the ‘why question’ and missed the rest of the explanation.

Years later, things started to click for me, and I realized that it wasn’t the fault of the education system but rather my way of thinking. As a high-context person, I’m inclined to bottom-up thinking, not top-down thinking. It also explains why during my college years, I told my friends that I was studying logic. For me, the insights I gained were a accumulation of logical matters.

After graduating, I became a part-time lecturer in various business subjects because, even in hindsight, I wanted to prevent others from not getting the right explanation for subjects I consider important.

During my first job, thanks to associate professor J.M. (Boy) van de Wiel, I went through a process of unlearning regarding the learned thinking of management schools about organizational design and learned to think in processes. In the years that followed, I gained a lot of experience in various organizations in different countries and in profit, non-profit, political, and government sectors; where I was able to develop myself into the world’s best (and only ;o) Firm Simplifier.